Unsupervised methods - Dimensionality reduction

Overview

Teaching: 30 min

Exercises: 30 minQuestions

How can we perform unsupervised learning with dimensionality reduction techniques such as Principle Component Analysis (PCA) and t-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE)?

Objectives

Recall that most data is inherently multidimensional

Understand that reducing the number of dimensions can simplify modelling and allow classifications to be performed.

Recall that PCA is a popular technique for dimensionality reduction.

Recall that t-SNE is another technique for dimensionality reduction.

Apply PCA and t-SNE with Scikit Learn to an example dataset.

Evaluate the relative peformance of PCA and t-SNE.

Dimensionality Reduction

Dimensionality reduction techniques involve the selection or transformation of input features to create a more concise representation of the data, thus enabling the capture of essential patterns and variations while reducing noise and redundancy. They are applied to “high-dimensional” datasets, or data containing many features/predictors.

Dimensionality reduction techniques are useful in the context of machine learning problems for several reasons:

- Avoids overfitting effects: It can be difficult to find general trends in data when fitting a model to high-dimensional dataset. As the number of model coefficients begins to approach the number of observations used to train the model, we greatly increase our risk of simply memorizing the training data.

- Pattern discovery: They can reveal hidden patterns, clusters, or structures that might not be evident in the original high-dimensional space

- Data visualization: High-dimensional data can be challenging to visualize and interpret directly. Dimensionality reduction methods, such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA) or t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE), project data onto a lower-dimensional space while preserving important patterns and relationships. This allows you to create 2D or 3D visualizations that can provide insights into the data’s structure.

The potential downsides of using dimensionality reduction techniques include:

- Oversimplifications: When we reduce dimensionality of our data, we are removing some information from the data. The goal is to remove only noise or uninteresting patterns of variation. If we remove too much, we may remove signal from the data and miss important/interesting relationships.

- Complexity and parameter tuning: Some dimensionality reduction techniques, such as t-SNE or autoencoders, can be complex to implement and require careful parameter tuning. Selecting the right parameters can be challenging and may not always lead to optimal results.

- Interpretability: Reduced-dimensional representations may be less interpretable than the original features. Understanding the meaning or significance of the new components or dimensions can be challenging, especially when dealing with complex models like neural networks.

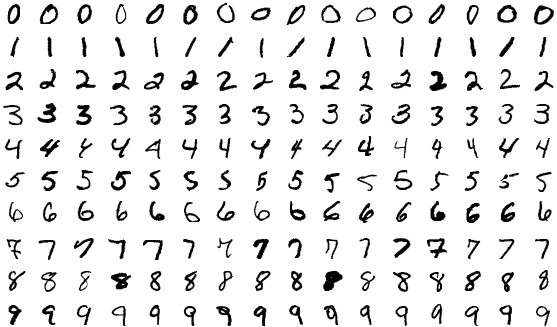

As seen in the last episode, general clustering algorithms work well with low-dimensional data. In this episode we see how higher-dimensional data, such as images of handwritten text or numbers, can be processed with dimensionality reduction techniques to make the datasets more accessible for other modelling techniques. The dataset we will be using is the Scikit-Learn subset of the Modified National Institute of Standards and Technology (MNIST) dataset.

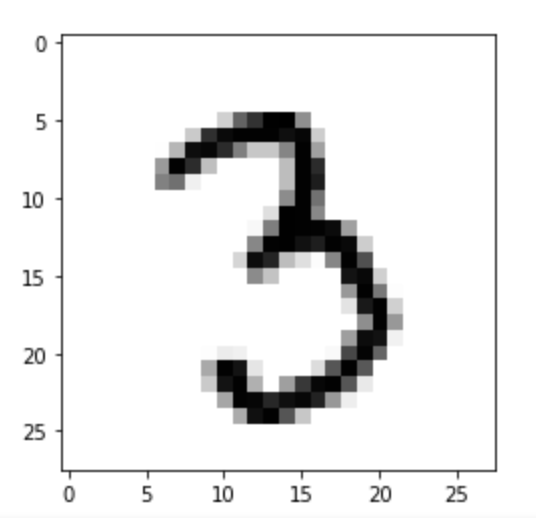

The MNIST dataset contains 70,000 images of handwritten numbers, and are labelled from 0-9 with the number that each image contains. Each image is a greyscale and 28x28 pixels in size for a total of 784 pixels per image. Each pixel can take a value between 0-255 (8bits). When dealing with a series of images in machine learning we consider each pixel to be a feature that varies according to each of the sample images. Our previous penguin dataset only had no more than 7 features to train with, however even a small 28x28 MNIST image has as much as 784 features (pixels) to work with.

To make this episode a bit less computationally intensive, the Scikit-Learn example that we will work with is a smaller sample of 1797 images. Each image is 8x8 in size for a total of 64 pixels per image, resulting in 64 features for us to work with. The pixels can take a value between 0-15 (4bits). Let’s retrieve and inspect the Scikit-Learn dataset with the following code:

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import sklearn.cluster as skl_cluster

from sklearn import manifold, decomposition, datasets

# Let's define these here to avoid repetitive code

def plots_labels(data, labels):

tx = data[:, 0]

ty = data[:, 1]

fig = plt.figure(1, figsize=(4, 4))

plt.scatter(tx, ty, edgecolor='k', c=labels)

plt.show()

def plot_clusters(data, clusters, Kmean):

tx = data[:, 0]

ty = data[:, 1]

fig = plt.figure(1, figsize=(4, 4))

plt.scatter(tx, ty, s=5, linewidth=0, c=clusters)

for cluster_x, cluster_y in Kmean.cluster_centers_:

plt.scatter(cluster_x, cluster_y, s=100, c='r', marker='x')

plt.show()

def plot_clusters_labels(data, labels):

tx = data[:, 0]

ty = data[:, 1]

# with labels

fig = plt.figure(1, figsize=(5, 4))

plt.scatter(tx, ty, c=labels, cmap="nipy_spectral",

edgecolor='k', label=labels)

plt.colorbar(boundaries=np.arange(11)-0.5).set_ticks(np.arange(10))

plt.show()

Next lets load in the digits dataset,

# load in dataset as a Pandas Dataframe, return X and Y

features, labels = datasets.load_digits(return_X_y=True, as_frame=True)

print(features.shape, labels.shape)

print(labels)

features.head()

Dimensionality reduction with Scikit-Learn

We will look at two commonly used techniques for dimensionality reduction: Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and t-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE). Both of these techniques are supported by Scikit-Learn.

Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

PCA is a data transformation technique that allows you to represent variance across variables more efficiently.

Using Scikit-Learn lets apply PCA in a relatively simple way.

Specifically, PCA does rotations of data matrix (N observations x C features) in a two dimensional array to decompose the array into vectors that are orthogonal and can be ordered according to the amount of information/variance they carry. After transforming the data with PCA, each new variable (or pricipal component) can be thought of as a linear combination of several of the original variables.

- PCA, at its core, is a data transformation technique

- Allows us to more efficiently represent the variability present in the data

- It does this by linearly combining variables into new variables called principal component scores

- The new transformed variables are all “orthogonal” to one another, meaning there is no redundancy or correlation between variables.

For more in depth explanations of PCA please see the following links:

- https://builtin.com/data-science/step-step-explanation-principal-component-analysis

- https://scikit-learn.org/stable/modules/decomposition.html#pca

In our digits example PCA allows us to reduce our 64 features in the MNIST dataset images to a smaller number of dimensional representations, while still retaining the majority of our variance/relational data to the point that we can still distinugish the individual digits.

Let’s apply PCA to the MNIST dataset and retain the two most-major components:

# PCA with 2 components

pca = decomposition.PCA(n_components=2)

x_pca = pca.fit_transform(features)

print(x_pca.shape)

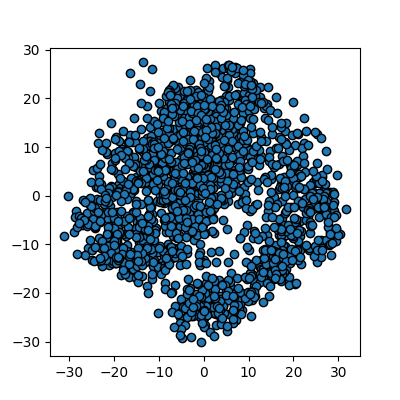

This returns us an array of 1797x2 where the 2 remaining columns(our new “features” or “dimensions”) contain vector representations of the first principle components (column 0) and second principle components (column 1) for each of the images. We can plot these two new features against each other:

# We are passing None becuase it is an unlabelled plot

plots_labels(x_pca, None)

We now have a 2D representation of our 64D dataset that we can work with instead. Let’s try some quick K-means clustering on our 2D representation of the data. Because we already have some knowledge about our data we can set k=10 for the 10 digits present in the dataset.

Kmean = skl_cluster.KMeans(n_clusters=10)

Kmean.fit(x_pca)

clusters = Kmean.predict(x_pca)

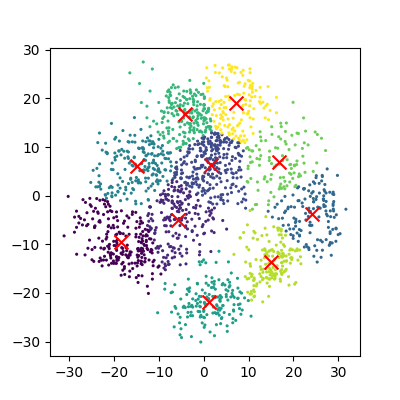

plot_clusters(x_pca, clusters, Kmean)

And now we can compare how these clusters look against our actual image labels by colour coding our first scatter plot:

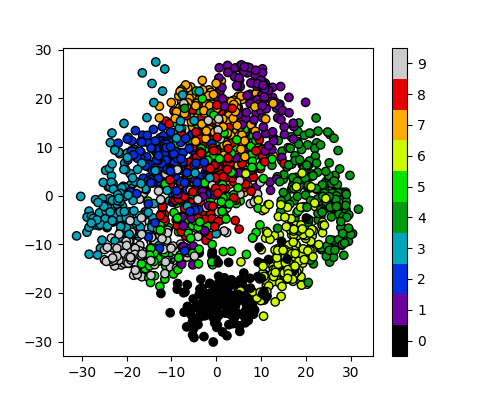

plot_clusters_labels(x_pca, labels)

PCA has done a valiant effort to reduce the dimensionality of our problem from 64D to 2D while still retaining some of our key structural information. We can see that the digits 0,1,4, and 6 cluster up reasonably well even using a simple k-means test. However it does look like there is still quite a bit of overlap between the remaining digits, especially for the digits 5 and 8. The clustering is from perfect in the largest “blob”, but not a bad effort from PCA given the substantial dimensionality reduction.

It’s worth noting that PCA does not handle outlier data well primarily due to global preservation of structural information, and so we will now look at a more complex form of learning that we can apply to this problem.

t-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE)

t-SNE is a powerful example of manifold learning - a non-deterministic non-linear approach to dimensionality reduction. Manifold learning tasks are based on the idea that the dimension of many datasets is artificially high. This is likely the case for our MNIST dataset, as the corner pixels of our images are unlikely to contain digit data, and thus those dimensions are almost negligable compared with others.

The versatility of the algorithm in transforming the underlying structural information into lower-order projections makes t-SNE applicable to a wide range of research domains.

For more in depth explanations of t-SNE and manifold learning please see the following links which also contain som very nice visual examples of manifold learning in action:

- https://thedatafrog.com/en/articles/visualizing-datasets/

- https://scikit-learn.org/stable/modules/manifold.html

Scikit-Learn allows us to apply t-SNE in a relatively simple way. Lets code and apply t-SNE to the MNIST dataset in the same manner that we did for the PCA example, and reduce the data down from 64D to 2D again:

# t-SNE embedding

# initialising with "pca" explicitly preserves global structure

tsne = manifold.TSNE(n_components=2, init='pca', random_state = 0)

x_tsne = tsne.fit_transform(features)

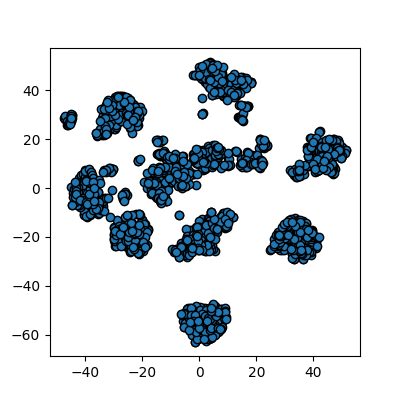

plots_labels(x_tsne, None)

It looks like t-SNE has done a much better job of splitting our data up into clusters using only a 2D representation of the data. Once again, let’s run a simple k-means clustering on this new 2D representation, and compare with the actual color-labelled data:

Kmean = skl_cluster.KMeans(n_clusters=10)

Kmean.fit(x_tsne)

clusters = Kmean.predict(x_tsne)

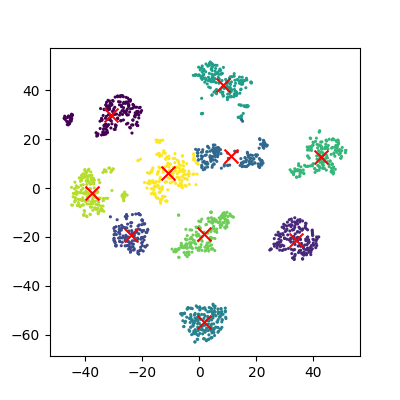

plot_clusters(x_tsne, clusters, Kmean)

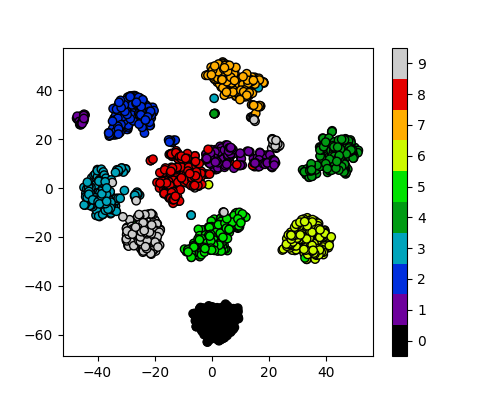

plot_clusters_labels(x_tsne, labels)

It looks like t-SNE has successfully separated out our digits into accurate clusters using as little as a 2D representation and a simple k-means clustering algorithm. It has worked so well that you can clearly see several clusters which can be modelled, whereas for our PCA representation we needed to rely heavily on the knowledge that we had 10 types of digits to cluster.

Additionally, if we had run k-means on all 64 dimensions this would likely still be computing away, whereas we have already broken down our dataset into accurate clusters, with only a handful of outliers and potential misidentifications (remember, a good ML model isn’t a perfect model!)

The major drawback of applying t-SNE to datasets is the large computational requirement. Furthermore, hyper-parameter tuning of t-SNE usually requires some trial and error to perfect.

Our example here is still a relatively simple example of 8x8 images and not very typical of the modern problems that can now be solved in the field of ML and DL. To account for even higher-order input data, neural networks were developed to more accurately extract feature information.

Exercise: Working in three dimensions

The above example has considered only two dimensions since humans can visualize two dimensions very well. However, there can be cases where a dataset requires more than two dimensions to be appropriately decomposed. Modify the above programs to use three dimensions and create appropriate plots. Do three dimensions allow one to better distinguish between the digits?

Solution

from mpl_toolkits.mplot3d import Axes3D # PCA pca = decomposition.PCA(n_components=3) pca.fit(features) x_pca = pca.transform(features) fig = plt.figure(1, figsize=(4, 4)) ax = fig.add_subplot(projection='3d') ax.scatter(x_pca[:, 0], x_pca[:, 1], x_pca[:, 2], c=labels, cmap=plt.cm.nipy_spectral, s=9, lw=0) plt.show()

# t-SNE embedding tsne = manifold.TSNE(n_components=3, init='pca', random_state = 0) x_tsne = tsne.fit_transform(features) fig = plt.figure(1, figsize=(4, 4)) ax = fig.add_subplot(projection='3d') ax.scatter(x_tsne[:, 0], x_tsne[:, 1], x_tsne[:, 2], c=labels, cmap=plt.cm.nipy_spectral, s=9, lw=0) plt.show()

Exercise: Parameters

Look up parameters that can be changed in PCA and t-SNE, and experiment with these. How do they change your resulting plots? Might the choice of parameters lead you to make different conclusions about your data?

Exercise: Other algorithms

There are other algorithms that can be used for doing dimensionality reduction (for example the Higher Order Singular Value Decomposition (HOSVD)). Do an internet search for some of these and examine the example data that they are used on. Are there cases where they do poorly? What level of care might you need to use before applying such methods for automation in critical scenarios? What about for interactive data exploration?

Key Points

PCA is a linear dimensionality reduction technique for tabular data

t-SNE is another dimensionality reduction technique for tabular data that is more general than PCA